Source: Daily Express, September 17, 1936, pp. 12-17

Note: PDF scan of this newspaper article can be downloaded here

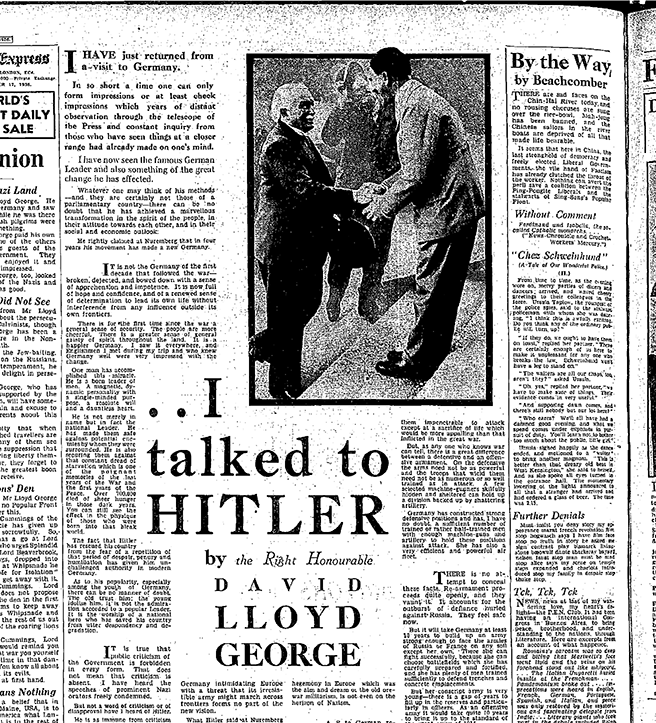

I talked to Hitler

by the Right Honourable David Lloyd George

I have just returned from a visit to Germany.

In so short a time one can only form impressions or at least check impressions which years of distant observation through the telescope of the Press and constant inquiry from those who have seen things at a closer range had already made on one's mind.

I have now seen the famous German Leader and also something of the great change he has effected.

Whatever one may think of his methods—and they are certainly not those of a parliamentary country—there can be no doubt that he has achieved a marvelous transformation in the spirit of the people, in their attitude towards each other, and in their social and economic outlook.

He rightly claimed at Nuremberg that in four years his movement has made a new Germany.

It is not the Germany of the first decade that followed the war - broken, dejected, and bowed down with a sense of apprehension and impotence. It is now full of hope and confidence, and of a renewed sense of determination to lead its own life without interference from any influence outside its own frontiers.

There is for the first time since the war a general sense of security. The people are more cheerful. There is a greater sense of general gaiety of spirit throughout the land. It is a happier Germany. I saw it everywhere, and Englishmen I met during my trip and who knew Germany well were very impressed with the change.

One man has accomplished this miracle. He is a born leader of men. A magnetic, dynamic personality with a single-minded purpose, a resolute will and a dauntless heart.

He is not merely in name but in fact the national Leader. He has made them safe against potential enemies by whom they were surrounded. He is also securing them against that constant dread of starvation, which is one of the poignant memories of the last years of the War and the first years of the Peace. Over 700,000 died of sheer hunger in those dark years. You can still see the effect in the physique of those who were born into that bleak world.

The fact that Hitler has rescued his country from the fear of a repetition of that period of despair, penury and humiliation has given him unchallenged authority in modern Germany.

As to his popularity, especially among the youth of Germany, there can be no manner of doubt. The old trust him; the young idolize him. It is not the admiration accorded to a popular Leader. It is the worship of a national hero who has saved his country from utter despondency and degradation.

It is true that public criticism of the Government is forbidden in every form. That does not mean that criticism is absent. I have heard the speeches of prominent Nazi orators freely condemned.

But not a word of criticism or of disapproval have I heard of Hitler.

He is as immune from criticism as a king in a monarchical country. He is something more. He is the George Washington of Germany—the man who won for his country independence from all her oppressors.

To those who have not actually seen and sensed the way Hitler reigns over the heart and mind of Germany this description may appear extravagant. All the same, it is the bare truth. This great people will work better, sacrifice more, and, if necessary, fight with greater resolution because Hitler asks them to do so. Those who do not comprehend this central fact cannot judge the present possibilities of modem Germany.

On the other hand, those who imagine that Germany has swung back to its old Imperialist temper cannot have any understanding of the character of the change. The idea of a Germany intimidating Europe with a threat that its irresistible army might march across frontiers forms no part of the new vision.

What Hitler said at Nuremberg is true. The Germans will resist to the death every invader of their own country, but they have no longer the desire themselves to invade any other land.

The leaders of modern Germany know too well that Europe is too formidable a proposition to be overrun and trampled down by any single nation, however powerful may be its armaments. They have learned that lesson in the war.

Hitler fought in the ranks throughout the war, and knows from personal experience what war means. He also knows too well that the odds are even heavier today against an aggressor than they were at that time.

What was then Austria would now be in the main hostile to the ideals of 1914. The Germans are under no illusions about Italy. They also are aware that the Russian Army is in every respect far more efficient than it was in 1914.

The establishment of a German hegemony in Europe which was the aim and dream of the old pre-war militarism, is not even on the horizon of Nazism.

But, as any one who knows war can tell, there is a great difference between a defensive and an offensive armament. On the defensive the arms need not be as powerful and the troops that wield them need not be as numerous or so well trained as in attack. A few selected machine-gunners skilfully hidden and sheltered can hold up a division backed up by shattering artillery.

Germany has constructed strong defensive positions and has, I have no doubt, a sufficient number of trained or rather half-trained men with enough machine-guns and artillery to hold these positions against attack. She has also a very efficient and powerful air fleet.

There is no attempt to conceal these facts. Re-armament proceeds quite openly, and they want it. It accounts for the outburst of defiance hurled against Russia. They feel safe now.

But it will take Germany at least 10 years to build up an army strong enough to face the armies of Russia or France on any soil except her own. There she can fight successfully, because she can choose battlefields which she has carefully prepared and fortified, and she has plenty of men trained sufficiently to defend trenches and concrete emplacements.

But her conscript army is very young - there is a gap of years to fill up in the reserves and particularly in officers. As an offensive army it would take quite 10 years to bring it up to the standard of the great army of 1914.

But any attempt to repeat Poincare's antics in the Rühr would now be met with a fanatical resistance from myriads of brave men who count death for the Fatherland not a sacrifice but a glory.

This is the new temper of the German youth. There is almost a religious fervour about their faith in the movement and its Leader.

That impressed me more than anything I witnessed during my short visit to the new Germany. There was a revivalist atmosphere. It has had an extraordinary effect in unifying the nation.

Catholic and Protestant, Prussian and Bavarian, employer and workman, rich and poor, have been consolidated into one people. Religious, provincial and class origins no longer divide the nation. There is a passion for unity born of dire necessity.

The divisions which followed the collapse of 1918 made Germany impotent to face her problems, internal and external. That is why the clash of rival passions is not only deprecated, but temporarily suppressed.

Public condemnation of the Government is censored as ruthlessly as it is in a state of war. To a Briton accustomed to generations of free speech and a free Press this restraint on liberty is repellent, but in Germany, where such freedom is not as deeply rooted as it is here, the nation acquiesces not because it is afraid to protest, but because it has suffered so much from dissension that the vast majority think it must be temporarily called off at all costs.

Freedom of criticism, is therefore for the time being in suspense. German unity is the ideal and the idol of the moment, and not liberty.

I found everywhere a fierce and uncompromising hostility to Russian Bolshevism, coupled with a genuine admiration for the British people with a profound desire for a better and friendlier understanding with them.

The Germans have definitely made up their minds never to quarrel with us again. Nor have they any vindictive feelings towards the French. They have altogether put out of their minds any desire for the restoration of Alsace-Lorraine.

But there is a real hatred and fear of Russian Bolshevism, and unfortunately it is growing in intensity. It constitutes the driving force of their international and military policy. Their private and public talk is full of it. Wherever you go you need not wait long before you hear the word "Bolschewismus," and it recurs again and again with a wearying reiteration.

Their eyes are concentrated on the East as if they were watching intently for the breaking of the day of wrath. Against this they are preparing with German thoroughness.

This fear is not put on. High and low they are convinced there is every reason for apprehension. They have a dread of the great army which has been built up in Russia in recent years.

An exceptionally violent anti-German campaign of abuse printed in the Russian official Press and propelled by the official Moscow radio has revived the suspicion in Germany that the Soviet Government are contemplating mischief against the Fatherland.

Unfortunately the German leaders set this down to the influence of prominent Russian Jews, and thus the anti-Jewish sentiment is being once more stirred up just as it was fading into turpitude. The German temperament takes no more delight in persecution than does the Briton, and the native good humor of the German people soon relapses into tolerance after a display of ill-temper.

Every well-wisher of Germany— and I count myself among them— earnestly pray that Goebbels's ranting speeches will not provoke another anti-Jewish manifestation. It would do much to wither the verdant blades of good will which were growing so healthily in the scorched battleground which once separated great civilized nations.

But we should do wisely not to attach extravagant importance to recent outbursts against Russia. The fact of the matter is, the German Government in its relations with Russia is now in the stage from which we ourselves have only just emerged.

We can all recall the time when Moscow, through its official publications, Press and radio, made atrocious personal attacks on individual British Ministers—Austen Chamberlain, Ramsay MacDonald and Churchill—and denounced our political and economic system as organized slavery.

We started this campaign of calumny by stigmatizing their leaders as assassins, their economic system as brigandage, their social and religious attitude and behavior as an orgy of immorality and atheism.

This has been the common form of diplomatic relationship between Communist Russia and the rest of the world on both sides. We must not forget that even when we had a Russian Minister here we actually sent the police to raid one of the official buildings of the Russian Embassy to rummage for treason in their hampers of frozen butter.

No one imagined that was intended as a preliminary or a provocation to war on either side. The slinging of scurrilities between Germany and Russia is only the usual language of diplomacy to which all countries have been accustomed during the last 20 years where Communist Russia is concerned.

It is important we should realize for the sake of our peace of mind that a repetition of this unseemly slanging match does not in the least portend war. Germany is no more ready to invade Russia than she is for a military expedition to the moon.

What then did the Führer mean when he contrasted the rich but under-cultivated lands of the Ukraine and Siberia and the inexhaustible mineral resources of the Urals with the poverty of German soil? It was simply a Nazi retort to the accusation hurled by the Soviets as to the miseries of the peasantry and workers of Germany under Nazi rule.

Hitler replied by taunting the Soviets with the wretched use they were making of the enormous resources of their own country. In comparison with the Nazi achievement in the land whose natural wealth was relatively poor.

He and his followers have a horror of Bolshevism and undoubtedly underrate the great things the Soviets have accomplished in their vast country. The Bolsheviks retaliate by understating Hitler's services to Germany.

It is only an interchange of abusive amenities between two authoritarian Governments. But it does not mean war between them.

I have no space in which to give a catalogue of the schemes which are being carried through to develop the resources of Germany and to improve the conditions of life for her people. They are immense and they are successful.

I would only wish to say here that I am more convinced than ever, that the free country to which I have returned is capable of achieving greater things in that direction if its rulers would only pluck up courage and set their minds boldly to the task.