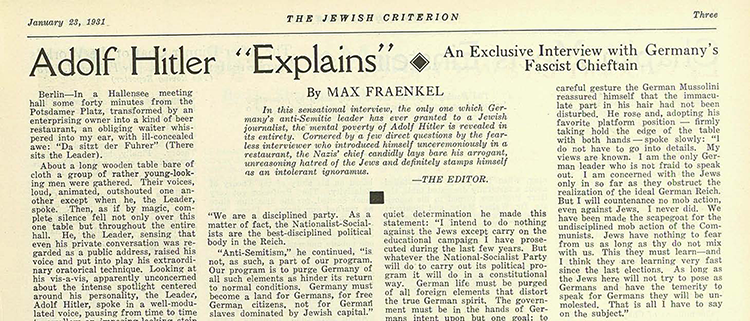

Author: Max Fraenkel

Source: The Jewish Criterion, January 23, 1931. Click to Download

Note: This rare interview is referenced on very few places on the Internet, so I am not sure of its legitimacy although the newspaper itself is very much real

Adolf Hitler "Explains"

An Exclusive Interview with Germany's Fascist Chieftain

In this sensational interview, the only one which Germany's anti-Semitic leader has ever granted to a Jewish journalist, the mental poverty of Adolf Hitler is revealed in its entirety. Cornered by a few direct questions by the fearless interviewer who introduced himself unceremoniously in a restaurant, the Nazis' chief candidly lays bare his arrogant unreasoning hatred of the Jews and definitely stamps himself as an intolerant ignoramus. - The Editor

Berlin—In a Hallensee meeting hall some forty minutes from the Potsdamer Platz, transformed by an enterprising owner into a kind of beer restaurant, an obliging waiter whispered into my ear, with ill-concealed awe: "Da sitzt der Fuhrer" (There sits the Leader).

About a long wooden table bare of cloth a group of rather young-looking men were gathered. Their voices, loud, animated, outshouted one another except when he, the Leader, spoke. Then, as if by magic, complete silence fell not only over this one table but throughout the entire hall. He, the Leader, sensing that even his private conversation was regarded as a public address, raised his voice and put into play his extraordinary oratorical technique. Looking at his vis-a-vis, apparently unconcerned about the intense spotlight centered around his personality, the Leader, Adolf Hitler, spoke in a well-modulated voice, pausing from time to time to swallow an imposing-looking stem of beer.

Adolf Hitler's pictures do not do justice to the uncontested leader of the National Socialists. He looks much younger than his forty-one years. His athletic figure, his military bearing, his fresh complexion, his authoritative expression, which is enhanced by his thin, pointed, aggressive mustache, give one the impression of a German officer of pre-war days in civilian clothes.

When I introduced myself he stiffened. His entourage studied his countenance so as to know whether to make room for me. But Hitler did not seem inclined to speak to a newspaper correspondent m front of his young followers. He motioned to the Oberkellner and asked him to show us into a sort of private office on the same floor. There, a little less stiffly but still business-like, he asked me: "What is it you want to know?"

My first question, without any introductory preamble, was: "Is anti-Semitism a plank of the political platform of the Nazis?"

Hitler blinked at my query, and asked: "Do you represent a Jewish paper?" I explained that I was interested in obtaining a clear idea of his stand because I was making a study of anti-Semitism in Europe. Speaking with a noticeable Bavarian accent, the leader of the Nazis then said:

"I don't like to give interviews. I am a newspaperman myself and know how easily one's words are distorted. But since you are here I shall answer some of your questions, it being understood that I represent my personal views. The rules of my party prohibit the issuing of statements unless they are approved by our inner council."

I was unable to suppress a smile as I thought of Hitler's dictatorial power. Guessing the reason for my apparent skepticism, Hitler added:

"We are a disciplined party. As a matter of fact, the Nationalist-Socialists are the best-disciplined political body in the Reich.

"Anti-Semitism," he continued, "is not, as such, a part of our program. Our program is to purge Germany of all such elements as hinder its return to normal conditions. Germany must become a land for Germans, for free German citizens, not for German slaves dominated by Jewish capital."

The interviewer interposed: "As one who has lived in Germany for many years I know that Jewish capital plays an unimportant role in the economic life of the country. In the great industries, in the manufacturing and of course in the agricultural phases of Germany life Jews play a minimal part. What, then, do you mean by "German slaves dominated by Jewish capital?"

The would-be dictator of Germany was in no hurry to reply. Slowly, emphasizing every word, he said: "When I speak of Jewish capital, Jewish politics and Jewish domination I do not necessarily mean Jews. I mean, rather, all that is not truly German. The Jews have infected culture and German politics with their views. By trying to transform themselves into Germans they have turned Germans into Jews. They influence business and politics with their internationalistic ideas. The only way in which Germans who have become infected with Judeophilia can be saved is by labeling everything un-German Jewish."

"In other words, you are making the German Jew the victim, the scapegoat of your policy," I observed.

"No," replied the Leader. "They are a real menace."

"How can less than one per cent of the total population be a threat to the nation? There are only about half a million Jews in this country of almost seventy millions," I continued.

"Your figures are not exactly correct, but a few tens of thousands one way or the other make little difference. However, how about the Communists in Russia? Though their percentage in the total population is smaller than that of the Jews here they control the country."

"What do you propose to do about this Jewish menace?" I countered.

Hitler smiled, but the smile did not soften his stem expression. With quiet determination he made this statement: "I intend to do nothing against the Jews except carry on the educational campaign I have prosecuted during the last few years. But whatever the National-Socialist Party will do to carry out its political program it will do in a constitutional way. German life must be purged of all foreign elements that distort the true German spirit. The government must be in the hands of Germans intent upon but one goal: to liberate Germany from its present slavery. This can be done by instilling into Germans their lost self-respect and their faith in their own abilities. The propaganda which we carry on is aimed to elevate German self-confidence."

"Are you serious when you advocate the wholesale expulsion of Jews from Germany?" I inquired squarely.

Unhesitatingly the Leader replied:

"I do want to get rid of"—he used the word loswerden—those Jews who since the War have invaded our country from Eastern Europe and undermined our morale by mad speculation, who are devoid of all patriotism and have made fortunes out of our national catastrophe. As for the rest, I merely want to limit their influence by passing legal prohibitions against their participation in the Government and by eliminating from public life such non-Jews as act as puppets for Jewish capital."

"Can you name any such 'puppets'?"

"I would call the entire Bruening Cabinet a Jewish cabinet. I qualify the Stressemann foreign policy a Jewish policy. I designate the Berlin police department as Jewish. The humiliating surrender of German interests to our former enemies is due entirely to Jewish influence."

"Do you, then, consider pacifism a Jewish quality or defect specifically?"

"I am a pacifist myself," was the surprising rejoinder of the man who seven years ago tried to capture the governmental reins of Bavarie by means of a military putsch. "By pacifism I" — he stressed the "I" in dramatic fashion — "understand the maintenance of peace as long as one's national honor is unsoiled. The Jewish view of peace, because of the international Jewish mind, means the surrender of all pride for the sake of financial interests."

"Sometimes the anti-Semites accuse the Jews of militarism," I remarked, "and sometimes they charge them with noxious pacifism; at other times the Jews are accused as destroyers of all law and order, while only the other day Count Salm, the uncle of your Austrian colleague Prince Starhemberg, called anti-Semitism a revolutionary movement because Jews always support the conservative property-loving classes of their country. How do you reconcile all this?"

By that time it appeared that Adolf Hitler was becoming annoyed at the persistent questioning. It seemed to dawn upon him that this interlocutor, notwithstanding his blond hair and blue eyes, must be a Jew. With a careful gesture the German Mussolini reassured himself that the immaculate part in his hair had not been disturbed. He rose and, adopting his favorite platform position — firmly taking hold the edge of the table with both hands — spoke slowly: "I do not have to go into details. My views are known. I am the only German leader who is not afraid to speak out. I am concerned with the Jews only in so far as they obstruct the realization of the ideal German Reich. But I will countenance no mob action, even against Jews. I never did. We have been made the scapegoat for the undisciplined mob action of the Communists. Jews have nothing to fear from us as long as thy do not mix with us. This they must learn—and I think they are learning very fast since the last elections. As long as the Jews here will not try to pose as Germans and have the temerity to speak for Germans they will be unmolested. That is all I have to say on the subject."

The leader of the second-largest parliamentary party in Germany, whose name has become synonymous with anti-Semitism throughout Central Europe, drew himself up, bowed slightly and strode out to rejoin his companions. As he approached his party rose and a youngster in a brown shirt with sleeve adorned with the swastika stretched out his arm in the traditional Fascist salute.